Three islanders from Lesbos — home of the ancient poet Sappho, who praised love between women — have taken a gay rights group to court for using the word lesbian in its name. …

'My sister can't say she is a Lesbian,' said Dimitris Lambrou. 'Our geographical designation has been usurped by certain ladies who have no connection whatsoever with Lesbos,' he said.

The three plaintiffs are seeking to have the group barred from using 'lesbian' in its name and filed a lawsuit on April 10.

Wednesday, April 30, 2008

Lesbos ladies launch lesbian lawsuit

Monday, April 21, 2008

Pay Attention! Brain Scanners Detect Slip-Ups Before You Do

A mindless mistake on a monotonous task may feel like a momentary glitch, but its mental roots run deep.

In a study [by Tom Eichele, a neuroscientist at the University of Bergen in Norway] published today in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, researchers used fMRI machines to record neurological patterns preceding careless errors.

The recordings revealed a cascade of shifting activity in the parts of the brain associated with focusing attention and maintaining routines. Researchers observed test subjects' minds going on autopilot up to half a minute before the subjects actually made mistakes, even though the subjects weren't aware of their own lapses of attention. …

Up to 30 seconds before Eichele's test subjects carelessly said that an arrow pointing in one direction was pointing in another, blood flow decreased in their posterior medial frontal cortex, a brain region associated with sustaining effort and focus.

At the same time, activity increased in the so-called default mode network — a region of the brain spanning the precuneus, retrosplenial cortex and anterior medial frontal cortex. The default mode network is associated with maintaining baseline routines, and tends to be most active during sleep and sedation.

In short, the conscious brain started to shut down while the system usually responsible for preventing that failed.

"This matches with our subjective perception of making mistakes on a boring task," said Michael Fox, a neuroscientist at Washington University in St. Louis who was not involved in the study. "As time goes on, you get more and more bored, and that builds up until you screw up. This study shows that scientifically.

Friday, April 18, 2008

Experts Agree that Capital Gains Tax Cuts Lose Revenue

During Wednesday’s Democratic presidential debate, Charles Gibson of ABC News made the following statements about capital gains taxes:

- “Bill Clinton in 1997 signed legislation that dropped the capital gains tax to 20 percent and George Bush has taken it down to 15 percent and in each instance when the rate dropped, revenues from the tax increased. The government took in more money.”

- “So why raise it [the capital gains rate] at all, especially given the fact that 100 million people in this country own stock and would be affected.”

These statements, echoed in a Wall Street Journal editorial today, are seriously misleading, as explained below.

Cutting capital gains rates reduces revenues over the long run. That’s the conclusion of the federal government’s official revenue-estimating agencies, as well as outside experts and the Bush Administration’s own Treasury Department.

- The non-partisan Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and the Joint Committee on Taxation have estimated that extending the capital gains tax cut enacted in 2003 would cost $100 billion over the next decade. The Administration’s Office of Management and Budget included a similar estimate in the President’s budget.

- After reviewing numerous studies of how investors respond to capital gains tax cuts, the non-partisan Congressional Research Service concluded that cutting capital gains taxes loses revenue over the long run.

- The Bush Administration Treasury Department examined the economic effects of extending the capital gains and dividend tax cuts. Even under the Treasury’s most optimistic scenario about the economic effects of these tax cuts, the tax cuts would not generate anywhere close to enough added economic growth to pay for themselves — and would thus lose money.

While a capital gains tax cut can lead investors to rush to “cash in” their capital gains when the lower rate first takes effect, it does not raise revenue over the long run.

- Especially when a capital gains cut is temporary, like the 2003 tax cut that Gibson cited, investors have a strong incentive to sell stocks and other assets in order to realize their capital gains before the capital gains tax rate increases. This can cause a short-term increase in capital gains tax revenues, as happened after the 2003 tax cut.

- Capital gains revenues also increased after 2003 because the stock market went up. But the stock market increase was not a result of the 2003 tax cut, as a study by Federal Reserve economists found. European stocks, which did not benefit from the U.S. capital gains tax cut, performed as well as stocks in the U.S. market in the period following the tax cut.

- To raise revenue over the long run, capital gains tax cuts would need to have extraordinary huge, positive effects on saving, investment, and economic growth that virtually no respected expert or institution believes they have. In fact, experts are not even sure that the long-term economic effects of these capital gains tax cuts are positive rather then negative.

One reason is that preferential tax rates for capital gains encourage tax sheltering, by creating incentives for taxpayers to take often-convoluted steps to reclassify ordinary income as capital gains. This is economically unproductive and wastes resources. The Urban-Brookings Tax Policy Center’s director Leonard Burman, one of the nation’s leading tax experts, has explained, “shelter investments are invariably lousy, unproductive ventures that would never exist but for tax benefits.” Burman has concluded that, “capital gains tax cuts are as likely to depress the economy as to stimulate it.”Middle-income families derive only a miniscule benefit from the 2003 cuts in capital gains and dividends.

Charles Gibson’s second statement — that 100 million Americans own stock and would be affected by a change in the capital gains tax rate — also is mistaken.

- Most middle-income Americans own much or all of their stock through 401(k)s, IRAs, or other tax-preferred saving accounts. They do not pay taxes when their stocks within those accounts go up, so a change in the tax rate doesn’t affect them.

Even among the minority of middle-class Americans who do benefit from the capital gains and dividend tax cuts, the benefits are very small. This is because capital gains and dividend income is highly concentrated at the very top of the income scale. The Tax Policy Center estimates that the highest-income 5 percent of U.S. households receive 83 percent of total capital gains income.

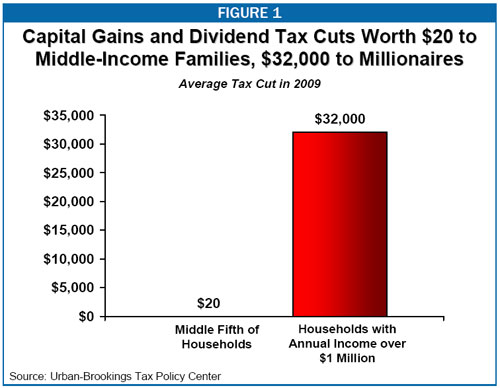

- According to the Tax Policy Center, the average household in the middle of the income spectrum received $20 from the 2003 capital gains and dividend tax cuts. The average household earning over $1 million received $32,000, or 1,600 times as much.

The myth that tax cuts pay for themselves hinders a debate on the nation’s budget priorities — and its serious long-term budget problems and the tough choices we must make to address them — by creating the illusion of a free lunch. Such free lunches do not exist. Capital gains tax cuts either make the nation’s daunting long-term budget problems even more severe or consume scarce resources (primarily to the benefit of the most well-off) that could otherwise be used for purposes such as moving toward universal health coverage or improving the educational system.

# # #

The Center on Budget and Policy Priorities is a nonprofit, nonpartisan research organization and policy institute that conducts research and analysis on a range of government policies and programs. It is supported primarily by foundation grants.

Thursday, April 17, 2008

Global Warming: The Greenland Factor

So how fast is Greenland melting? To figure that out scientists have been clocking the speed at which ice sheets are sliding to the sea, and have shown that the speed has increased. New research published Apr. 17 in the online journal Science Express explains how this actually occurs. Here's what happens: Big lakes of meltwater form on the surface of the ice in the summer. The pressure from the water then creates cracks in the ice sheet that go all the way down to bedrock, more than half a mile below. The water then gushes down through the ice in a cataclysmic flow rivaling Niagara Falls.

Down at the bedrock, the water actually lifts up the massive ice sheet and acts like grease, doubling the speed of the glaciers' journey over the bedrock to the sea. 'It matters,' says Richard Alley, professor of geosciences at Pennsylvania State University, and an ice-sheet expert: 'It is not 'run for the hills, we are doomed,' but this tells us that loss of the Greenland ice could happen in centuries, not millennia.'

Francis Collins, again

presents a good opportunity.

presents a good opportunity. For Francis Collins, head of the Human Genome Project and an evangelical Christian, scientific knowledge complements rather than contradicts belief in God. In his 2006 bestselling book, The Language of God: A Scientist Presents Evidence for Belief, Collins argues that advances in science present 'an opportunity for worship,' rather than a catalyst for doubt. Recently, the Pew Forum interviewed Dr. Collins about his views on science and religion.For the most part, I'll just present Collins' answers unless there is some ambiguity.

If you see God as the creator of the universe – in all of its amazing complexity, diversity and awesome beauty – then science, which is, of course, a means of exploring nature, also becomes a means of exploring God’s creative abilities. And so, for me, as a scientist who is also a religious believer, research activities that look like science can also be thought of as opportunities to worship.As I've said a number of times previously, the most sympathetic interpretation I have found for religious faith — other than dismissing it as an unconscious externalization of subjective experience — is that the subject matter of religion is outside empirical determination and is therefore not relevant to the material world. This seems to be more or less Collins' position, although I doubt that he would put it that way. This first answer suggests this position, namely that science explores nature and since God created nature, i.e., the universe, science explores "God's creative abilities." It doesn't seem to matter in any real sense whether "God created the universe" has any real meaning or truth value. Science certainly explores nature. The rest is outside of the realm in which we can say what the sentence means.

One can look at Genesis 1-2, for instance, and see that there is not just one but two stories of the creation of humanity, and those stories do not quite agree with each other. That alone ought to be reason enough to argue that the literal interpretation of every verse, in isolation from the rest of the Bible, can’t really be correct. Otherwise, the Bible is contradicting itself. …This is another subject I've written about. How should one do religious epistemology, i.e., how does one decide which statements to believe. Collins acknowledges that there is a problem, and he doesn't have an answer. But that doesn't seem to bother him. If I were confronted with a doctrine that included a number of self-contradictory statements, along with other statements that contradicted current ethical principles or empirical evidence, I would be bothered — or at least concerned about finding some approach to deciding which statements to believe. So I don't understand why being in such a situation doesn't bother Collins. But that seems to be the religious answer to everything. The less sense something makes, the more it confirms the mystery.

If Augustine, who was one of the most thoughtful, original thinkers about biblical interpretation that we’ve ever had, was unable to figure out what Genesis meant 1,600 years ago, why should we today insist that we know what it means.

If God has any meaning at all, God is at least in part outside of nature (unless you’re a pantheist). Science is limited in that its tools are only appropriate for the exploration of nature. Science can therefore certainly never discount the possibility of something outside of nature. To do so is a category error, basically using the wrong tools to ask the question.This brings us back to the first point: belief in God is outside science. But since science investigates everything which is within human experience, belief in God refers to something which is outside human experience. If that's the case, it doesn't matter whether one believes or not since we are unable to experience what belief is about. To my mind, that's a good definition of either fiction or meaninglessness.